Towards the end of October, Compass held an event series entitled “Build Back Better: How?”. A lot of good content to chew over from a range of voices talking about a range of ideas. In this post I attempt to weave together just some of what seem to be the most salient issues on the progressive agenda for a post-pandemic UK.

Giving People a Voice

A greater role for citizens in decision-making was one such recurring theme. In particular, Citizens’ Assemblies have gained a lot of traction in recent years, off the back of seemingly successful experiments in Ireland and elsewhere. Stuart White, an academic, talked attendees through the reasons for a CA (namely the desire to move on from referenda) and the advantages of the CA process.

The advantages include providing a route for politicians to reform the political system while avoiding the conflict of interest associated with changing the rules of the game – that is, the rules of their own game. For example, the voting system or House of Lords reform.

And anything the CA recommends will be more legitimate. Not driven by party political interests but rather the national interest, deliberative democracy in the form of CAs offer legitimacy in a way that transcends partisan agendas. Indeed, once implemented, these decisions would be difficult to overturn by politicians who simply didn’t like them.

CAs also offer a way for political groups to resolve internal disputes. Think EU exit for the Conservative Party, or electoral reform for progressive parties.

Sarah Allan from Involve, who helped run Climate Assembly UK this year, offered more practical benefits of CAs. Done right, they allow citizens with diverse experiences and backgrounds from right across the breadth of society to contribute to decision-making. The participants themselves enjoy an experiential benefit of contributing to decisions that affect them. And to other citizens, CA recommendations will inherently be treated more favourably than just another policy report from the Westminster bubble.

However, I noted CAs are not without their disadvantages. Most obviously, the Climate Assembly UK’s recommendations were non-binding. Decisions ought to be made ultimately by politicians who can be held accountable at the ballot box. White offered a formula of CA + referendum on final recommendations, which might side-step the involvement of politicians altogether. Though of course it was the messiness of referenda that a CA sought to avoid in the first place…

I did note a deeper criticism could be parsed from the contribution of Amy McDonnell, a representative from the campaign for the Climate and Ecological Emergency Bill. Whilst supportive of CAs, she argued that Climate Assembly UK didn’t go far enough in terms of scope and scale. The CEE Bill would ask a CA to work on an earlier deadline than the government, and also consider adaptation and biodiversity loss. It made me realise setting the right question, premise, scale and scope for CAs are also important for their legitimacy.

Good Leadership

Maybe we ought to make sure we elect the kind of leaders who set the right terms of reference. There was an event dedicated entirely to leadership and what ‘good leadership’ might look like.

Jamie Driscoll, Metro Mayor of North of Tyne, pointed out that a lot of what we hate to see in our politicians – needless hostility, aggression, constant need to undermine each other – owes a lot to the system in which they operate. Our House of Commons has been designed specifically for the two major parties to face off against each other. Our party system itself encourages tribalism. Our media thrives on conflict, so are only too happy to facilitate us-versus-them discourses.

A complete overhaul of this environment is probably setting our sights too high right now. In the meantime, however, we could try to change our expectations of our leaders. We should encourage politicians who are willing to admit when they’re wrong, willing to work with others, and show compassion and empathy. The ‘chest-thumping toxic macho culture’ of Westminster got a lot of mentions across all events, but so did Jacinda Ardern, Prime Minister of New Zealand, illustrating what might be possible.

Practically, this would mean a lot more reaching out to communities and the third sector. At the national level, this could mean involving advocacy organisations in CAs, but also a greater role for third parties (academics? advocates? trade unions?) in regular policy development. But perhaps more pressingly, central government should be willing to devolve to, and work with, local government.

And even at the local level, there is scope to reach out. The borough of Barking & Dagenham has invested heavily in a social infrastructure that incorporates third sector organisations linked to community residents, quite contrary to traditional bureaucratic structures. Council Leader Darren Rodwell explained this allowed them to respond much more quickly, and comprehensively, to the coronavirus pandemic than the levers pulled by central government. Surely this example is worth emulating by councils elsewhere?

A Domestic and Global Vision

An event based on globalisation underscored the point that any party – not just progressive ones – need to have a global vision as well as a domestic one. This is a corollary of living in an international system where decisions in other countries, or at the international table, impact us here (and vice versa). In no area is this more urgent than climate action, which also had its own panel.

Domestically, this year we have seen all sectors of society – communities, businesses and government – engaging in rapid, complete change in operations. The emergence of Mutual Aid groups, factories churning out PPE, and a partnership of fiscal and monetary policies to stabilise employment were just some of the examples given by Andrew Simms, Coordinator of the Rapid Transition Alliance. If we can muster up so much momentum, so quickly, in the midst of a lockdown, just imagine what we could do for the climate?

A renewed progressive vision for the country can go further. The Climate and Ecological Emergency Bill charts a blueprint more ambitious (and more substantive) than our current strategy. Attendees also heard from representatives from two intriguingly simple yet radical campaigns. One wanted to reclaim public space from corporate advertisers, to replace ads with whatever local residents would like to see more of instead. The other campaign wants to remove all cars from city life – even electric ones!

But decarbonisation and climate mitigation is a global crisis – in cause and effect. In truth there are some things we have little control over (political leadership in the major polluters for instance) but there are certain things we do have control over: our soft power, the values we demonstrate, and our leadership by example. Examples include the carbon budgeting method and the statutory Net Zero target.

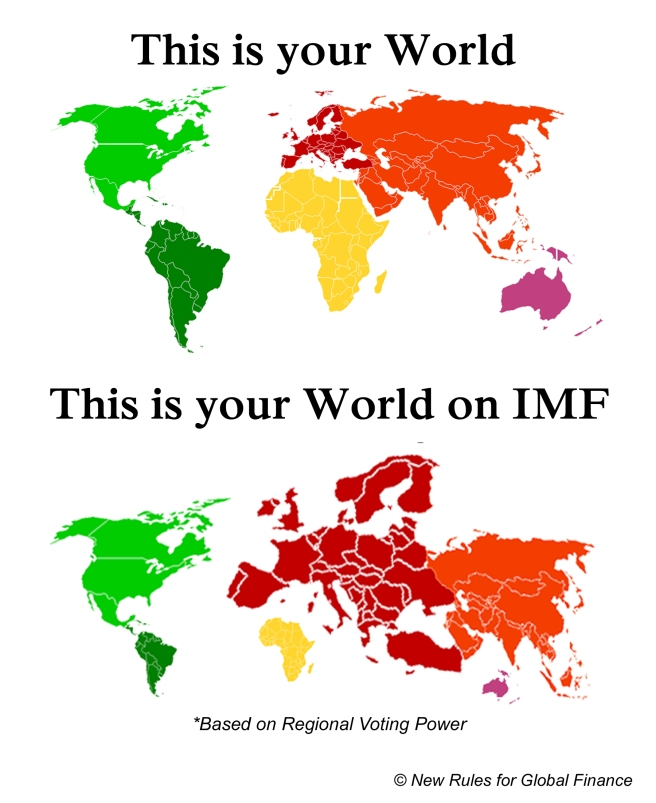

A progressive vision for the world would have to be much more radical, in the literal sense of the term: going to the core of the international system and reforming it root and branch. Existing international organisations in their current incarnations – the UN, IMF, et al – have a sketchy record in facilitating climate action, or indeed other progressive causes. And they’re distant from the citizens of the world, even the citizens of the major powers which are accused of manipulating them for their own purposes.

Whether reformed or overhauled, a progressive international system would require organisations which allowed more countries a say, as well as a more direct say for citizens. The academic Dena Freeman asked attendees to imagine a global parliament, for example, or the ability to petition for a particular issue akin to Citizens’ Initiatives. Such massive changes must necessarily be accompanied by a greater awareness of the international system and global citizenship education.

This is where I might get quite sceptical. Educating the public is easier said than done for issues of everyday relevance, let alone global politics. But I noted a sound-bite from Lisa Nandy MP, Labour spokeswoman for foreign affairs: “globalisation isn’t working for working people”, referring to the unexpected political developments we’ve seen in recent years. Maybe this sort of imaginative thinking is exactly what would allow people to ‘take back control’?

Plenty of food for thought all around. I look forward to seeing how the narratives around these ideas evolve as progressive parties start eyeing the next election. And of course I equally look forward to writing about these ideas in greater detail in the future.

Links to Event Recordings

- Build Back Better: How? (the full playlist)

- Connecting the Community: How? featuring Sotez Chowdhury, Darren Rodwell, chaired by Frances Foley

- Deliberating and Doing: How? featuring Sarah Allan, Amy McDonnell, Prof Stuart White, chaired by Frances Foley

- Globalisation: How? featuring Anthony Barnett, Dr Dena Freeman, Lisa Nandy MP, chaired by Neal Lawson

- Leading the Way: How? featuring Jamie Driscoll, Uffe Elbaek, Jennifer Nadel, Mandu Reid, chaired by Sue Goss

- Rapid Transition: How? featuring Hirra Khan Adeogun, Nicola Round, Andrew Simms, chaired by Frances Foley