“On Politics Live BBC political editor Laura Kuenssberg compared the situation to “the credit card, the national mortgage, everything absolutely maxed out”, adding that “for next few years, there is really no money”.”

Economists lambast BBC over ‘misleading’ UK debt coverage, City A.M.

Seeking a Narrative tries to avoid quick takes and reactionary posts, but I couldn’t quite help myself when one of our most prominent political reporters made such an error in a live broadcast to the nation. It echoes the household analogy that was used to devastating effect in the wake of the previous crisis, neutering the recovery.

In this post, I want to counter this false narrative. In particular, I write about why you cannot compare the government budget to the household budget. Consider it a companion piece to my previous post on why you shouldn’t worry about the deficit.

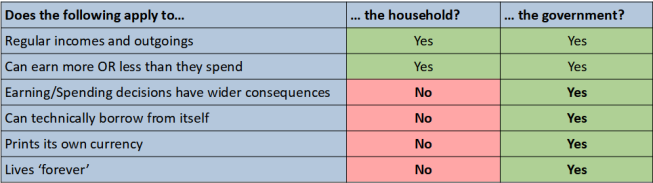

The household – that’s you and me as private individuals and families – has money coming in and going out on a regular basis. These incomes and expenditures usually have a monthly pattern (bills, wages, etc.). If monthly incomes are greater than expenditures, then the household has a ‘surplus’ and can add to their savings or pay down debt. If the reverse is true, the household is in ‘deficit’: it must either run down existing savings or take out a loan to cover the difference.

Loans are usually okay to fill in a gap every now and again, but reliance on loans is inadvisable. Unfortunately many households do have to rely on loans, sometimes even taking out new loans to pay back previous ones. The more loans a household takes out, the higher the interest rate they are likely to be charged. But eventually credit sources run out as confidence in the household’s ability to repay all this debt dissipates, and without further recourse they may have to declare bankruptcy.

This seems to make sense. And the course of our everyday lives confirms this logic even if we don’t experience it ourselves. What we do not have so much experience of is the management of public finances which don’t follow the same logic. Politicians use this asymmetry to their own advantage. What do they know that we don’t?

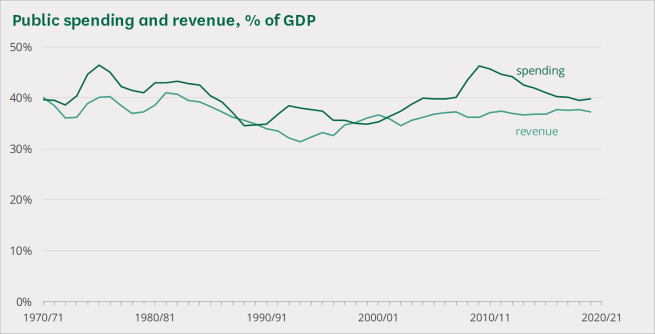

The government also has money coming in and going out on a regular basis. We usually talk about these in yearly terms, though various statistics are also collected monthly and quarterly. If revenues are greater than expenditure, the government runs a fiscal surplus, and can afford to pay down its pre-existing debt (or increase its reserves). If the government outspends collected revenues, it runs a deficit for that year and must use borrowing to fill the gap.

So far, so similar. The major divergence does occur at this point in the story, however, I will point out that already there is a difference with the household. This difference is that government spending can influence government revenue. The same cannot be said of the household.

For instance, if the government increases welfare payments for the poor, they then spend this money on goods and services which yield consumption taxes (like VAT). Note the reverse is also true: if the government reduces its injections into the economy, it will receive less in taxes, and also risks materially reducing everyone’s living standards. No individual household has that power.

That aside, the major divergence is in the nature of borrowing each entity undertakes.

In terms of official sources, households are limited to things like payday loans and credit cards from financial services providers. These loans must be repaid to avoid severe consequences.

Whom does the government borrow from? Mostly retail banks and financial institutions like pension funds. An increasing amount is also borrowed from the Bank of England, which, being another arm of the public sector, often isn’t even quoted in debt statistics.

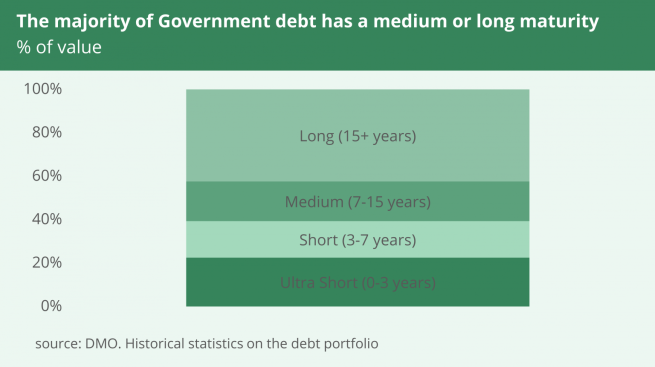

How does the government borrow? The instrument of borrowing is the bond. Bonds are IOU notes. The government says, “if you give me £100, I will give you £5 every year for a 50 year period, at the end of which I will return to you the initial £100”. In this example, the £100 is called the principal, the £5 is the coupon, 5% (£5/£100) is the yield or interest, and the 50 year period is the duration or maturity.

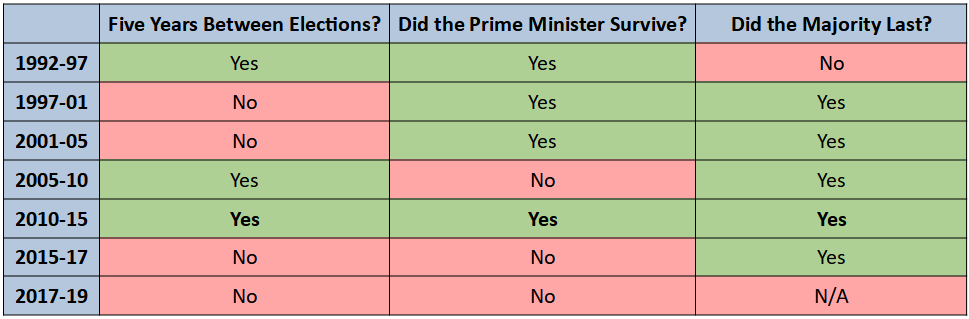

The maturity of bonds can vary, but the average of the current stock of bonds that have been issued is about 15 years. But governments usually last five years (even less these days). How does that work? Well, here’s the secret: when it does need to borrow, the government issues bonds that it knows it may not need to repay. Annual interest payments do happen, but the final repayment may not occur until a generation or two down the line, by a future government.

What does today’s government do? It pays interest payments, and the final repayments, on bonds issued by previous governments. The “government” is an entity that far outlasts any individual Chancellor, Spending Review period or parliamentary term.

The task of any given government is to manage the interest and principal repayments on the stock of bonds accumulated by its predecessors (the “national debt”), as well as issuing new bonds to fund its own spending gaps if applicable, including the need to borrow to repay previous debts.

The assumed infinite lifespan of government is what allows it to continue like this without worrying about repaying all of its debt. (I say ‘assumed’ because there is the possibility the state will collapse but, should that occur, I imagine we will have more pressing issues to tend to.)

If governments can just keep servicing debt like this then these bonds carry little risk – so borrowing more does not correlate with higher interest rates. In fact, if a country has control over its own money supply and issues bonds in its own currency there is hardly any risk at all.

But this does not apply to all governments, and that’s why Greece and Argentina are also false parallels to the UK. Greece, along with the rest of the Eurozone, cedes monetary sovereignty to the European Central Bank. Argentina issues bonds denominated in US dollars, over which it has no control. The UK is more like the US and Japan: large economies with large debts to match.

At this point hopefully you get the picture: the UK government’s borrowing is of a very different nature to that of the household. The table below summarises.

Though this is not to say the Treasury faces no constraint at all. A legitimate concern is the cost of interest payments. If interest payments keep rising then they will eat into an ever increasing portion of government revenues, thereby increasing the need to borrow just to pay interest, as opposed to funding public services and welfare provision.

It is this figure – interest payments as a proportion of revenues – that we ought to have debates and discussion about, not if the government has any money. I will return to these ideas in future posts.

Sources and Further Reading

- Letter to the BBC Director General Tim Davie signed by economists, complaining about Kuenssberg’s comments: Economists urge BBC to rethink ‘inappropriate’ reporting of UK economy

Official sources and statistics

- Debt Management Office’s latest Quarterly Review [mentioning average maturity of bonds being 15 years]: Quarterly Review July – September 2020

- House of Commons Library Insight on this year’s debt: Coronavirus: Government debt, an explainer

- House of Commons Library Research Briefing on debt statistics: Government borrowing, debt and debt interest: statistics

- House of Commons Library Research Briefing on the budget deficit: The budget deficit: a short guide

Commentary from professional economists

- Frances Coppola in Forbes provides the view from the US, considering the impacts of austerity: Governments Are Nothing Like Households

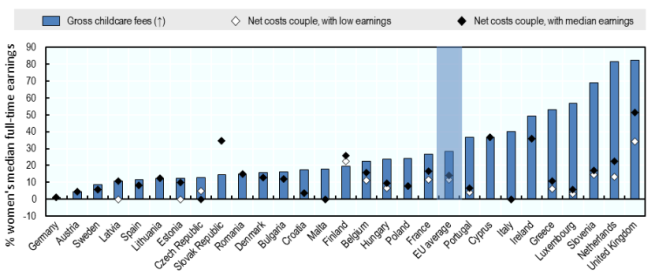

- Ann Pettifor wrote about this in The Guardian, with reference to how it holds women back: Philip Hammond ought to dispel the economic myths that hold women back

- New Economics Foundation blog on this topic: A government is not a household

- Positive Money blog on the weaponisation of the household fallacy: Claims of ending austerity ring hollow, unless we do away with the ‘household’ fallacy