Here is the follow up to my post that explained how the arguments in favour of First Past the Post have gotten weaker in recent years. This post will be more about the benefits of Proportional Representation particularly in the context of the 2019 General Election.

Note that PR isn’t a system per se but instead a type or category of system. In the same way that FPTP as a system falls into the category of ‘plurality’, there are different systems that could be labelled PR. In this post I will be advocating the principle of using a PR-type system, rather than for a specific system.

Proportionality

So let’s start with the biggest and most important (at least to me) point in favour of PR: proportionality. It’s in the name, folks.

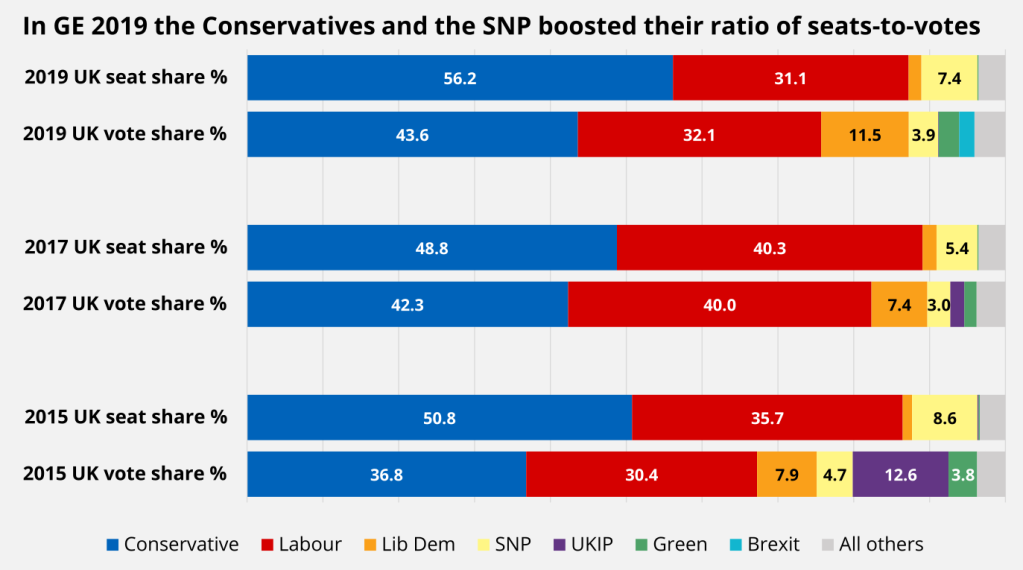

In 2019, the Conservatives achieved 44% of the vote, yet obtained 56% of the seats. Due to the nature of our political system, all you really need is 50% + 1 seat in the House of Commons to form a government – the extra 6% of seats actually does little besides insulating the government from minor rebellions.

Thus, it took 44% of voters to elect a majority government to rule over all of us for up to five years. In other words, most voters in 2019 chose a party that was not the winning party, but are nevertheless subjected to a single-party majority government. Another term for this is minority rule. This election wasn’t unique but standard fare with FPTP; only one election since World War II yielded a government that had more than 50% of the vote share.

A PR system would more closely align the national vote shares with seats in the Commons.

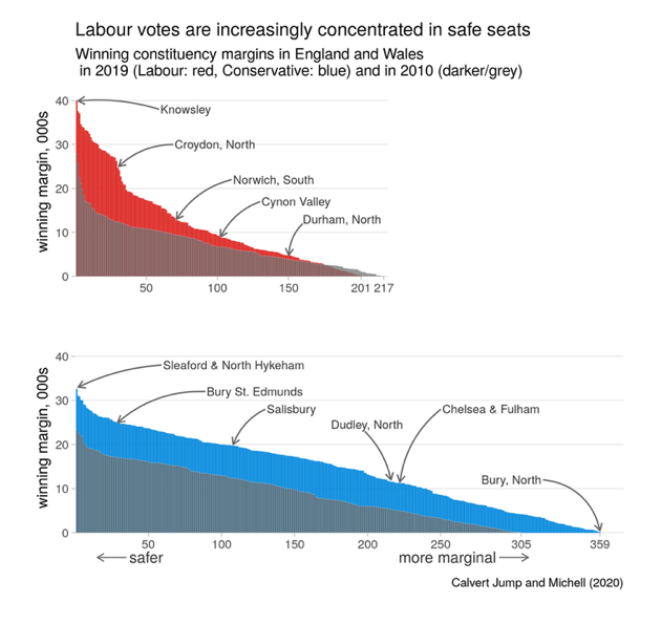

So, depending on the system, 44% of the votes would probably not yield a majority. Labour’s 31% of the vote coincidentally matched its 32% of seats in 2019, though of course this does not mean Labour voters should be satisfied as some of these will be excess votes for a winning candidate in some constituencies balanced by fruitless votes that will have gone to losing candidates in others.

This problem of ‘wasted votes’ – over 70% of all votes in 2019 – affects all parties to some degree and would be mitigated, if not completely eliminated, under a PR system.

Ultimately the principle I believe in is that only a majority of the vote share should lead to a majority government. Not only do we not have this, but a majority of votes are wasted, so that only around 30% of votes in 2019 mattered at all. I would argue this is undemocratic.

Voter Choice

A second point in favour of PR is the ability to give voters some choice. PR enables voters to exercise considerably more choice than just crossing one ‘x’ in one box to elect one candidate for one constituency.

A couple of examples may help here.

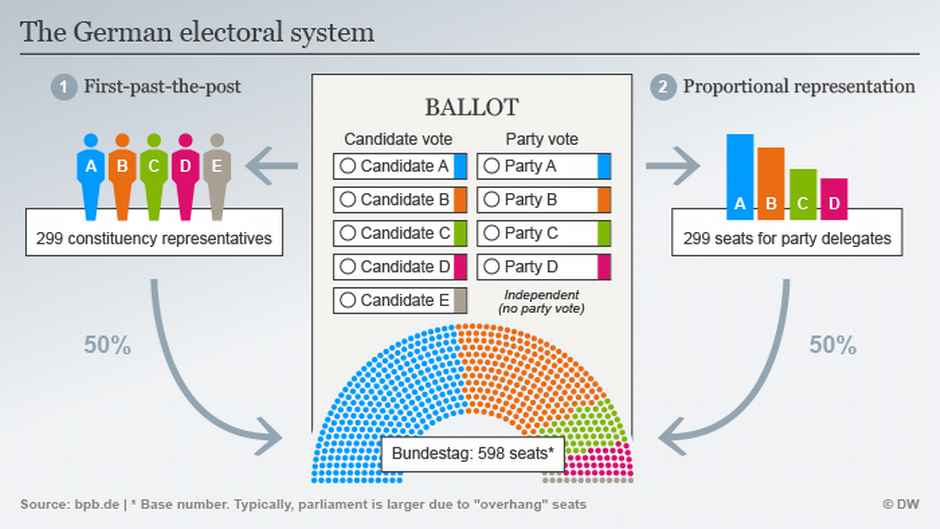

In Germany, the voting system for the primary chamber is Mixed Member PR. The system is also used for the devolved assemblies in Wales and Scotland. The ballot allows voters to pick one candidate for their local constituency, much like the FPTP ballot. However, a second part of the ballot allows a ‘top up’ vote for a party to represent your wider region. These top up votes translate into seats, meaning even if your local-constituency vote goes nowhere, your regional-constituency vote still contributes to the final seat tally.

Suppose you are a centrist and currently live in a Con-Lab marginal. Clearly your support for Lib Dem or independent candidates won’t go anywhere, and you are thus effectively disenfranchised. Under Mixed Member PR you would be able to voice your support for centrist candidates in the regional-constituency even if you think your local-constituency vote is going to waste.

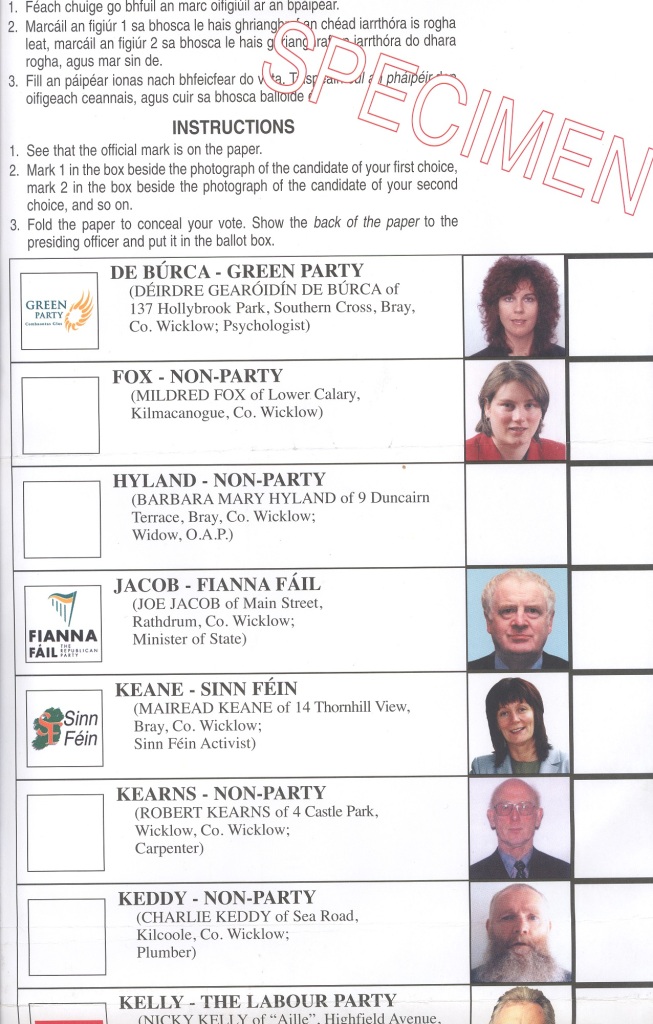

In Ireland, the voting system for the primary chamber is the Single Transferable Vote. A popular system on the island, it is also used for the devolved assembly in Northern Ireland. The STV ballot allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference for broader constituencies than exist under FPTP. Not only can you therefore voice your support for multiple parties in a ranking of your choice, you can choose to support different politicians within the same party.

Perhaps the party you usually support is currently being ruled by a faction with which you disagree on many positions. Under the current system you are again effectively disenfranchised; it’s the party candidate or the least worst alternative. Under STV you would be able to voice your support for the party’s candidates of another faction (assuming they choose to stand, of course), as well as other candidates with whom you sympathised, if you so wished.

Constituent Links

Another point in favour of moving to PR is that it would enhance the links between MPs and their constituents.

Note that some detractors of PR claim the exact opposite: that FPTP, where relatively small constituencies elect their MP, is the best choice for maintaining a local link between politicians and the areas (and voters) they represent. In fact, this analysis is superficial – and to see why, we need only turn again to the 2019 election.

Many MPs are elected on less than 50% of the vote, something almost all parties benefit from.

The seat of Sheffield Hallam was held by Labour by winning 35% of the vote share. The Conservatives won Ynys Mon with 36% of votes. In both of these constituencies, nearly two in three voters placed an ‘x’ in the box of another candidate – their votes completely wasted. It is incredibly difficult to claim that FPTP enables a close link between voters and representatives when most voters didn’t vote for them.

A proportional system would have allowed the election of representatives who did reflect voter preferences.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have ‘safe seats’, in which voters reliably vote one way.The Electoral Reform Society were able to correctly predict 316 out of 316 seats ahead of the 2019 election, half of all British seats. If seats are so uncompetitive, can we really be sure that the MP gives a toss one way or another about how constituents outside of their base feel? For voters of other parties, do they really feel a close link to their MP?

Under a proportional system, with multiple MPs representing voters, constituents have more than one MP to turn to – and, as a result of proportionality, those MPs will better reflect most voter preferences to boot.

A Better Politics?

A final point I’d like to make in this post is that FPTP is basically the most adversarial system we know of, and that it’s probably no coincidence that all the big parties love tearing into each other. PR could change that.

Now, I won’t claim that all problems of government would be done away with as soon as we replace the voting system; that we would get all the politicians we ‘deserve’; and the political process would immediately become much more sanguine and collegiate. Far from it.

What I do believe is that a shift to PR would be accompanied by a shift in the way politicians engage with each other, as well as what it would mean for their relationship with voters.

Politicians across the spectrum would behave, campaign and lead knowing that they may well have to work together some day, so it would be inadvisable to needlessly agitate, trip up, and fault each other. Perhaps they would instead spend this time reassuring the electorate that they have more in common with other politicians than they currently let on and focus on the issues that matter.

Voters would be able to vote (in at least one way) for the party and/or candidate they truly wish to vote for, without having to worry about their vote being wasted. MPs would better represent the diversity of political views among the electorate.

This may mean more parties, sure – but it would also mean right-leaning voters see their choices elected in the North West; left-leaning voters see theirs in the South East; and long-suffering voters of minor parties would finally see representation wherever they are.

Such a new arrangement might just allow for a revitalization of the political process and democratic engagement, enabling the breadth of views in society to be represented and work together to address the grand challenges we face: decisions surrounding decarbonisation; handling the impacts of demographic changes; learning and implementing the lessons from Covid-19; and many more.

Doesn’t that prospect alone make it worth a shot?

Related Reading

Join the Campaign

- Electoral Reform Society, campaigning for PR for the Commons and other bodies: Electoral Reform Society

- Make Votes Matter, campaigning for PR: Make Votes Matter

UK 2019 Election Analysis

- Electoral Reform Society’s post-mortem: The 2019 General Election: Voters Left Voiceless

- House of Commons Library’s brief analysis of votes and seats: General Election 2019: Turning votes into seats

Electoral Systems in the UK and Abroad

- DW’s explainer on the German electoral system (MMPR) ahead of their last election: How does the German general election work?

- Heinz Brandenburg offers projections of 2019 results if they occurred under the Dutch or German electoral systems: What would the British parliament look like under proportional representation?

- Institute for Government analysis on the different voting systems used in the UK: Electoral systems across the UK

- The Irish Times explains how the Irish electoral system (STV) works: Ireland’s voting system: How does it work and how should I use it?

- UK Parliament web page outlining the different voting systems used in the UK: Voting systems in the UK

Further Arguments In Favour of PR

- David Chadwick argues that PR would help elect a more socially representative Parliament: Can we break open the chumocracy?

- Jeremy Gilbert on how PR would affect the party system: Only electoral reform will rid the Labour party of factionalism

- Vote for Policies analysis shows that one vote for one party does not accurately reflect voter preferences: One vote, one party – but how much do we agree with the party we vote for?